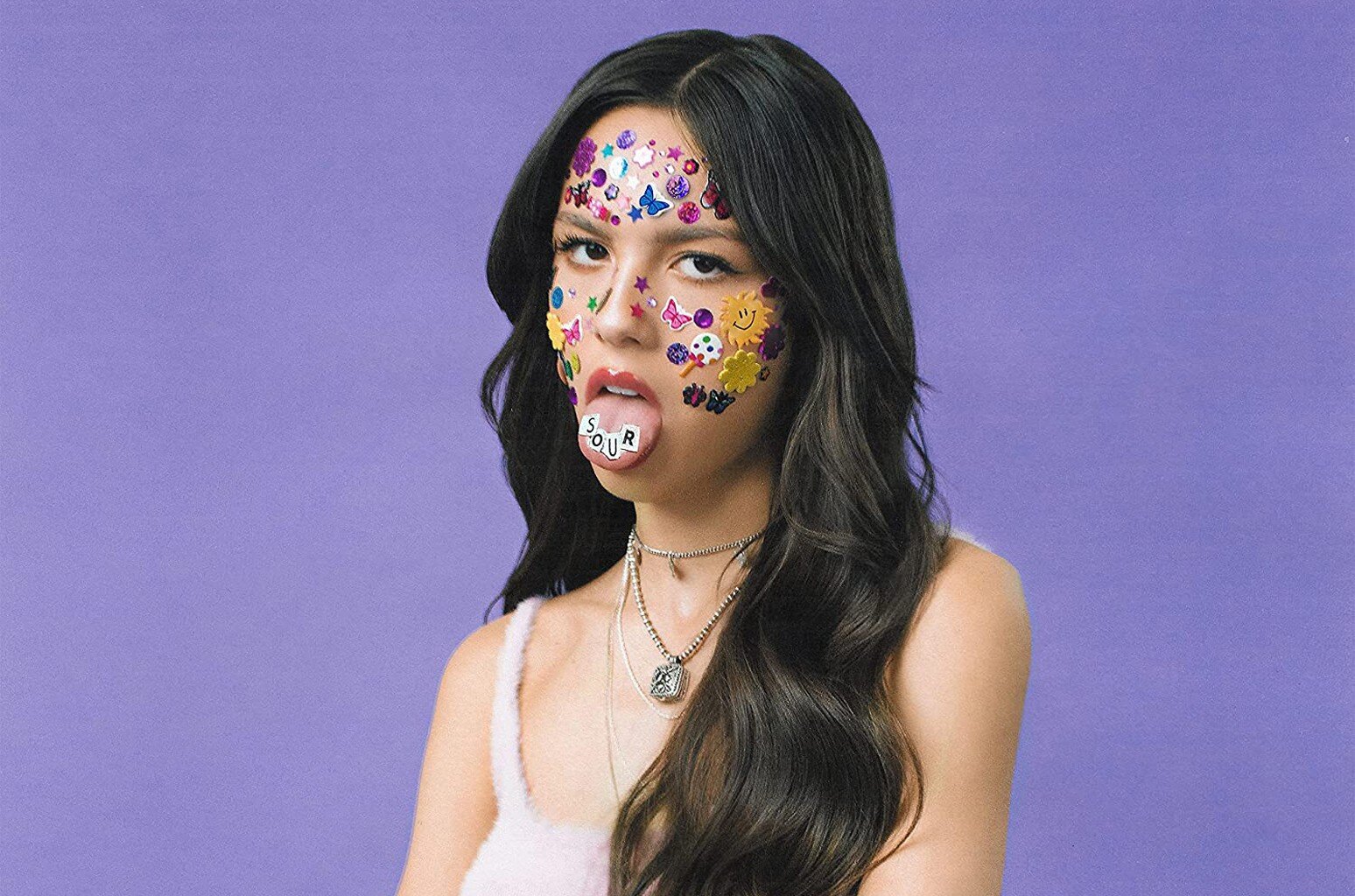

Olivia Rodrigo’s portrait for her album, Sour.

Is It All Over My Face?

The ideal of teenage perfection is being subverted everywhere we look – Claire Marie Healy digs into the stickers, grunge, and dirt of girlhood's new aesthetic to explore why.

The girls are bored so they are becoming monsters.

Or at least, that’s how it would appear. On a billboard on my high street, a singer called Billie Marten hovers above me with dirt and blades of grass coming out of her mouth, bringing to mind Estonian artist Ene-Liis Semper’s 1999 video work in which the artist places a flowering plant inside her mouth, including the soil. Rebecca Black, who became famous aged thirteen with the viral hit “Friday”, is currently promoting a new record with a cover that resembles a glamour shot for the wall of a 1960s hair salon – if it weren’t for the green gunge smeared over Black’s lips and smile. Rico Nasty’s forehead has appeared as a primal scream; Phoebe Bridgers is, ordinarily, a FunnyBones skeleton. And have you seen Petra Collins’ work recently? Having spent too long stuck inside the four walls of their teenage bedrooms, her girl-subjects are now more likely to be crawling up them. They’ve discovered lip liner, and grown elf ears, or alien antennae; they’ve definitely got into BDSM.

Photography by Petra Collins from Fairy Tales released by Rizzoli New York, 2021. Images © Petra Collins

Through Collins’ steamed-up lens we spot one of her recent collaborators, Olivia Rodrigo, whom the photographer has shot as a vengeful cheerleader in a blazing bedroom for the video for ‘good 4 u’ (in the girls’ world, lower case usage is always preferable). But I am more interested in the cover art for the 18-year-old’s record-breaking debut album, Sour. Here is Rodrigo, complete with perfectly tousled hair, nails and clothes, wearing an assortment of stickers in the shape of butterflies, sunshine and stars on her face. Her stare is equivalent to an eye-roll, and she sticks her tongue out, or rather, lets it hang.

Not fully monstrous, and pretty but not traditionally so, how can we read this image, and what is its impact? What can be said about all these girls’ mutations, if the idea of them feels inextricable from their power as a marketing tool?

Olivia Rodrigo, good 4 u, directed by Petra Collins

For feminist film academic Rosalind Galt, “pretty” – distinct from “ugly”, of course, but also distinct from “beautiful” – is a potential site for subversion in moving images. Speaking of the surface prettiness of Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, she writes that if one reads the film as “something other than a discourse on girly frivolity, it is possible to read its emphasis on the decorative as precisely the location of its political intervention.”

Such a position shifts Rodrigo’s face and tongue decor somewhere beyond mere styling choice. The stickers become a formal strategy, one that takes up the signs of the pretty to transmit a certain message. The stickers, after all, are deliberately childlike and cute. They’re a relative, probably, of the Starface pimple patches, designed to heal zits in a way that doesn’t just try and pretend like the spots aren’t there in the first place. In this way, the stickers work to deliberately flag up that Olivia Rodrigo is still just a girl, and a Disney Channel girl at that – an 18-year-old who wants you to know she is aware of the conditions of her fame’s origins.

“Olivia Rodrigo’s Sour portrait conjures a girlified world of objects in order to say, yes, those objects belong to us – to girls.”

You can’t read the album art without considering Instagram filters, too, which allow the generation that adores Rodrigo to re-actualise themselves as a more airbrushed version of themselves – but, more interestingly, as versions that have freckles, devil horns, and colourful stickers on their face. Contrary to the observations of many outsiders, the aesthetic of the Instagram filter isn’t only a tool in service of the tyranny of self-improvement: it’s a potential space for play with, and against, actual beauty norms.

Rodrigo’s stickers are the physical manifestation of this practice, refracted, by and large, into the social media space once more through the record’s promotion. Besides – who has ever felt like their actual teenage face is the best representation of who they really feel they are? The stickers, then, form a strategy that is inextricable from the condition of all girlhood/s: the simultaneous desire to hide, and to stand out, all at once.

Starface Acne Patches.

Olivia Rodrigo’s Sour portrait performs a kind of construction of girlhood in order to defend its practices. It’s not merely nostalgic, but self-aware. It conjures a girlified world of objects in order to say, yes, those objects belong to us – to girls. With one hand, it invites us to project our preconceptions of what a young-girl starlet is, and what she is for; but with the other hand, it pushes us back, asks us to look again.

With this image, Rodrigo is undoubtedly operating in the terrain of the pretty with her stickered face: she is skinny, glossy, perfect. But though the complex web of marketing strategy behind the image is probably incalculable, when it comes to how we encounter it, Sour is also a singular beauty moment – one which concentrates all the ideas of coming-of-age, personal style, self-actualisation, rebellion, nostalgia and consumerism that fuel contemporary girlhood/s today. Call it the equivalent of a driver’s license, rather than wondering which seat to take.