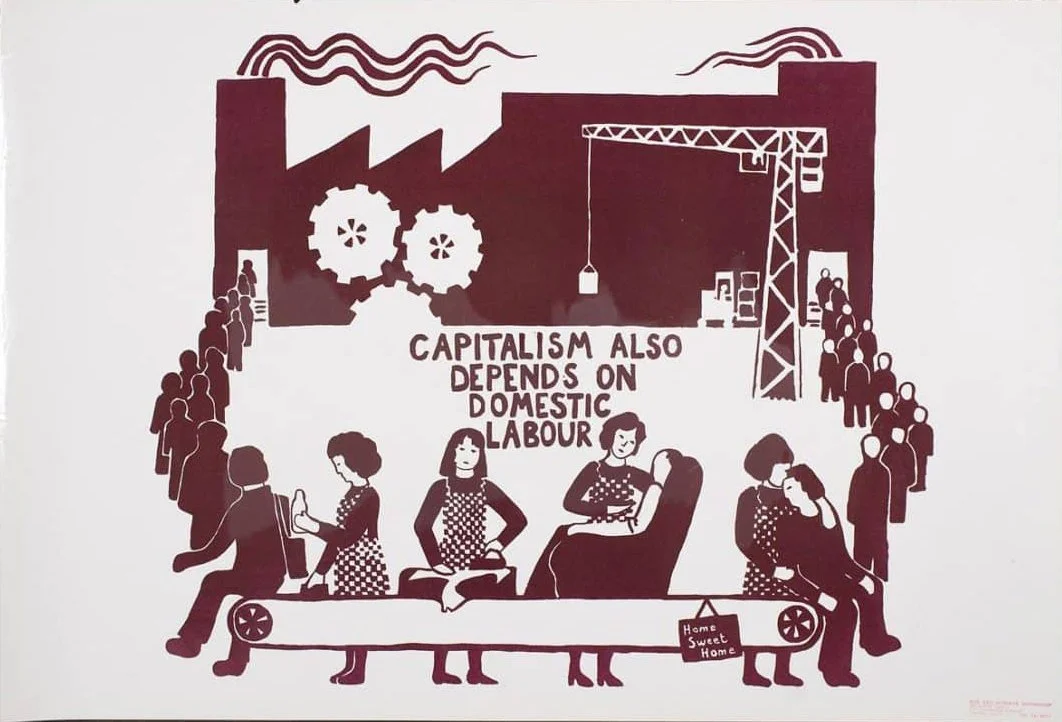

Poster from the See Red Women’s Workshop.

Essential Labour

Why we need to look at mothering and care work as the most essential labour a person can do, and why it’s ok to feel conflicted about doing it.

Words by Candice Pires

During the pandemic, US writer Angela Garbes entered the hours she’d spent caring for her family and home into an online income calculator. The calculator assigned an hourly amount to different household tasks; her annual wage came up to over $300,000. She wasn’t being paid for her labour, but it enabled her husband to work for money.

In Garbes’ new book, Essential Labor, she argues that the global economy is driven just as much by domestic labour – “happening in nurseries, laundry rooms, performed on hands and knees” – as it is by what society deems as traditional workplaces. And that domestic labour is essential, creative and influential.

Garbes is a first-generation Filipino-American. She details her own mother’s relationship to care work and traces the demands of mothering on women of colour in a global context of migration and exploitation. In the US, childcare work is performed disproportionately by women of colour; they make up 20 per cent of the population but 40 per cent of childcare workers.

For Garbes, the pandemic became an opportunity to find meaning and acknowledge the importance of mothering. She takes the hardest parts of what mothers have been through these last two years and explores how to use it to nurture ourselves and the next generation.

How did the practical mechanics of mothering change for you in the pandemic?

When the pandemic started, my daughters were five and two and went to preschool every day from 8:30am to 5:00pm. I was working on a book under contract for July 2020. Then suddenly, I was with my children uninterrupted without support, besides my spouse, for four months. One month into the pandemic I felt, “There’s no way I can do this.”

For all the conversations that my husband and I have about how to split domestic work equally, being a freelance writer, I wasn’t pulling in a regular pay cheque or providing us with employment healthcare benefits, so it was clear that we needed to prioritise my husband’s work. I took on a lot more domestic work.

Angela Garbes at home.

How did you react to that?

Early on, I thought, “What’s the most important work I could be doing right now? It’s not writing, it’s taking care of my family.” I knew that logically and it gave me direction. But two months in, that changed to, “Oh my God, this isn’t enough for me,” and I felt terrible. I didn’t know how to make sense of those two sides of me. A lot of this book is me working that out.

What I did realise is that yes, everyone should have the opportunity to pursue the work or interests they want, but really, mothering and care work—keeping ourselves and our people alive—is the most important work that humans have to do.

“The pandemic made me see care can be boring and deeply meaningful. It’s not either/or. ”

You talk about finding meaning in mothering. How did you do that?

The pandemic made me see care can be boring and deeply meaningful. It’s not either/or. When there’s no way to outsource domestic work and you have to do it all, no matter how meaningful you might think it is, it also feels like drudgery. It’s sense-deadening. Claustrophobic. You’re just, “Here I am, down on my hands and knees with a sponge in my hand cleaning the toilet bowl.” But the work’s inescapable. Someone has to do it, whether it’s you or someone you pay.

And so I was thinking, “How do I remind myself this is meaningful?” And I find great hope in parenting because there are so many things that I want for our society which I don’t know are possible in my lifetime, but could be possible in my children’s. I pushed that thought further, to, “How do I make sure those things are possible?” Part of it is raising people who understand from an early age the things I felt I came late to, like a full sense of bodily autonomy, that healthcare is a human right, that you can be any person that you want to be. And it clicked: “That’s what parenting is.” On a very small level, we can instil those values in kids as we mother. That’s meaningful.

“It’s powerful to remind mothers and women that they are essential workers. Without us taking care of children and the sick, our society shuts down. ”

As a society, we don’t classify mothering as traditional “work”, why is that?

I think that it’s capitalism. Not to idealise the past, but around the world people used to live more communally. When we privatised labour for an individual wage, people who wanted to make a profit needed a workforce that was unpaid. In these early laws, women were considered property and because biologically, female bodies birth the next generation, it’s easy to assign domestic and reproductive labour to them. There was this 1970s graphic, I think it was used during the Wages for Housework campaigns in the US and Europe, but it’s a picture of a factory and it says “Capitalism also depends on domestic labour”. I think about that a lot.

A Wages for Housework march, 1977

What can mothers learn from the power of organised workers and collective action?

It’s powerful to remind mothers and women that they are essential workers. The pandemic showed that. Without us doing domestic labour, without us taking care of children and the sick, our society kind of shut down. And it’s powerful to talk to other people about yourself as a worker, to begin to talk to your children about it. Saying, “You need to say thank you to me for doing this. I do it because I love you and I’m not going to stop, but it is work for me to get your dinner on the table and to clean it up.”

The other thing, which is hard for a lot of women to accept, is that we are not that different from the people we hire to do this work. We are not different from house cleaners and nannies and laundry people. The idea that some work is more valuable than others is a myth we’re asked to buy into that falsely teaches us that some people are less worthy than others.

People are starting to see collective action as the way to achieve things. When you are able to have solidarity with domestic workers who are severely underpaid with minimal worker protections, you can build from there.

How did your experience of your mother being a nurse shape your view of the work of caring?

My mother worked almost all of my childhood as a hospice nurse, taking care of dying patients. My father did autopsies. Death was the backdrop of growing up. But I was privileged enough to go through most of my life taking care work for granted. When I really felt its importance is after I became a mother. I started thinking, “How on earth do I have a professional job, feel fulfilled and take care of my daughter? How do I spend time with her?”

It became clear to me when we were looking at doing a nanny share that we needed to pay the nanny a decent wage. It had to be a minimum of $20 an hour, which is not even that much. And I thought, “Why am I insisting on this being valued?” Part of it is because as a woman of colour we were hiring another woman of colour and I didn’t want to feel like we were exploiting this worker.

I’ve always been interested in situating motherhood and care work in a larger context. Thinking about my mother, she was a professional carer and, yes, there’s schooling involved in that, but she was really a woman of colour. When I started looking into the history, I realised she became a nurse because of American imperialism that created a racialised and gendered workforce.

“The noun (motherhood) can feel limiting and confined to people who identify as mothers. And the work of raising children should never fall exclusively on women and mothers. ”

You talk about Filipino people being the care workers of the world. What do you mean by that?

Foreign remittances are over 10% of the Philippines’ gross domestic product. It’s just part of life there; to take care of your family, a lot of Filipinos leave. Filipinos speak great English, because we were an American colony. They were primed to be workers and then the government there took advantage and started sending them away. Filipinos are care workers here in the United States, in Europe, all over the world. They work on ships, they work as domestic labour throughout the Middle East, throughout Asia.

What’s the difference between mothering and motherhood?

Mothering is work any person can do. You don’t have to be a parent. I like it as a verb because it holds the infinite factions that are included in taking care of home and people. I thought about this a lot after reflecting on some of the responses to my first book, Like a Mother, that picked up on inclusive language.

Dani McClain’s book We Live for the We has informed my thinking. She talks about using the verb mothering as opposed to the noun motherhood. The noun can feel limiting and confined to people who identify as mothers. And the work of raising children should never fall exclusively on women and mothers.

Essential Labour by Angela Garbes is out in May, more info here.